- Home

- Robert Wang

The Opium Lord's Daughter Page 15

The Opium Lord's Daughter Read online

Page 15

“Sister Su-Mei, Sister Maria, a word, please.” Mother Amanda’s face was white with shock. Her chest heaved as she tried to take a breath. “I have bad news.”

Su-Mei wasn’t sure she could take any more news of any kind after Mr. Higgins’s declaration. The surprise of it had put her father’s absence completely out of her mind, at least. “What is it, Mother Amanda?”

“Oh, Sister Su-Mei, I just heard from one of Master Jardine’s men who arrived in Macau this morning. He said your father has been arrested, and he and your whole family are to be executed for high treason against the empire!”

Su-Mei blinked hard as she stared at Mother Amanda, trying to digest the words she’d just heard. It was as if Mother Amanda were speaking English, or something even more incomprehensible.

“They can’t arrest him,” she finally blurted out. “He is the son of a level one guan magistrate!”

“Master Jardine’s man said that an imperial special emissary from Peking with special powers is in Canton to rid the Celestial Empire of opium, and it is he who has arrested your father.”

“And put him to death? But why? I don’t understand!”

“Sister Su-Mei, your entire family is to be put to death. And this emissary and his men are looking for you!”

Su-Mei began to sob. “Is my brother Da Ping arrested also? And my grandfather—what of him? Surely they can’t execute him! He is a powerful man in Peking. How can this be happening?” The room spun around her, and she grabbed for the nearest support, which happened to be Pai Chu.

“Sister Su-Mei, I don’t know the answers,” said Mother Amanda, with tears in her eyes. “But you are safe here for now in this house of God, and we will find out more soon.”

This doesn’t make any sense, Su-Mei thought. Honorable Father may have been dealing with the opium traders, but so is half of Canton! Will this emissary execute the entire city? “I have to return to Canton and see what I can do,” she said. “I can’t hide here while my family waits for a death sentence. Or I could go to Peking and speak with Honorable Grandfather. He could intercede with the emperor.” Her thoughts were racing.

Mother Amanda put her hands on Su-Mei’s shoulders. “My child, it is unwise to make decisions when you have just suffered a shock. Why don’t we wait a few days and see what news comes from Canton? God will show us the way to proceed.”

“Can God stop my family’s execution, Mother Amanda? Will he hear my prayers?” Su-Mei asked, her face bathed with tears.

“Oh, my child, I cannot say.”

Mother Amanda suggested that Pai Chu sleep in Su-Mei’s room that night to calm her nerves and keep her company, and she was delighted to comply.

“God will protect you, Su-Mei, because you are kind and you have renounced your sins before him,” she said. “But I don’t know what will happen to the rest of your family. You must be patient, my dear friend. God’s will be done.” Pai Chu crossed herself. Su-Mei’s pain was her pain, and she would have given anything to comfort her.

“Maybe God is punishing Honorable Father for his sins,” Su-Mei said. “But if God is forgiving, and God is love, then why won’t God forgive Honorable Father and let him live to repent?”

“Su-Mei, there may be a greater purpose that we cannot know. Remember, God works in mysterious ways that we can never understand.”

“Will you pray with me, Pai Chu? I need God’s guidance more now than ever.”

“Of course, my dearest,” said Pai Chu, kneeling beside her. She grasped Su-Mei’s hand, the very same one that the foreign devil had touched without permission, and began to recite the rosary. When she finished, she added a special prayer to Mother Mary to protect Su-Mei and keep her from harm.

Mother Amanda knocked gently at Su-Mei’s door. “The English gentleman is here to see you, Sister Su-Mei.” Su-Mei started awake. She couldn’t remember falling asleep, and here it was already nine o’clock in the morning.

“Please tell Master Higgins that Su-Mei is unwell and unable to see him,” Pai Chu replied before Su-Mei had a chance to speak.

At three o’clock that afternoon, Su-Mei happened to see Higgins still waiting outside the convent doors. The flowers in his hands were beginning to wilt. She hurried to the doors and stepped outside.

“Meesta Heegans, I so solly. I not talk this day.”

“Miss Lee, it is of no consequence. I only wanted to make sure I didn’t upset you with the things I said yesterday.”

Su-Mei’s heart felt like it was made of wood. Not even the prospect of Mr. Higgins’s love for her could lift her mood. “Oh, sir, I have give so bad news from Canton.”

“Miss Lee, I am so sorry!” Higgins exclaimed. “Is it your family? Is anyone ill?”

Su-Mei could see how worried Higgins was, and she was also a tiny bit flattered that he had waited for her all day in front of the convent. I can trust this man; I don’t care what Pai Chu says. But how to tell him in English?

“Onnabul Fada, he—men take him. He do bad things.”

Higgins struggled to understand. “What? Do you mean he is in trouble with the magistrate?”

“I not know word. Fada, Mada, all fami-ee—kiu.”

“You are saying that your entire family is dead!? That can’t be what you mean!” Higgins, without thinking, reached out a hand to take her arm.

Su-Mei responded miserably. “Soon they be Zhixing,” she said, knowing he wouldn’t know that word.

“Miss Lee! How can I help?” Higgins said, not understanding. “Perhaps Mr. Jardine’s men can help since your father is a business associate. Please allow me to send a message at once! Mr. Jardine is en route to England, but I’m sure someone in his offices can do something.”

“No, no!” said Su-Mei. “It becoz fada and Engish bisis. Because of yapian! What Engish sell!”

Higgins paled. “Miss Lee, I don’t know what to say! Please, if there is anything at all I may do for you—I came to tell you that my ship sails tomorrow for Canton, and then to England when the winds favor our return in a few months. I wanted to let you know before I left, so you wouldn’t think that I no longer wished to see you—after I…” He faltered into silence.

Su-Mei had stopped listening after two important words. “You go Canton? Tomo—after day? I can come?”

“Miss Lee, I would have to ask permission from the captain. It would be most irregular to take on a passenger, but these are extraordinary circumstances.” Mixed in with his concern was a tiny beacon of joy. Was this the first step toward journeying to England as man and wife?

“Pleeze! I need go Canton, see my fami-ee before…” she trailed off.

“I will speak to the captain, explain your urgent need, and I’ll be back as soon as I can!” He thrust the wilted flowers, forgotten until now, into her hands. “Good day, Miss Lee! I shall not fail you!”

Su-Mei watched him race out of the courtyard, the bouquet of tropical blooms crushed to her chest.

“They will arrest you too if you go to Canton,” Pai Chu informed her grimly. “And then you’ll be executed right alongside your parents and brother! I cannot let you do this! What were you thinking?” And why did you agree to go with that foreign devil—alone? “In any event, Mother Amanda will never permit it,” she said flatly. “You can’t go to another city with a strange man and no chaperone.”

“I must go, Pai Chu! I have to try. I can’t just hide in a convent and wait for the news that my family is dead.” Su-Mei thought she’d cried all her tears, but more began to fall.

“Then I’m coming with you,” Pai Chu said. “But we can’t tell Mother Amanda.”

“No, I won’t drag you into this, Pai Chu. It will cause you trouble with Mother Amanda, and you’re still not well enough to travel. Besides, Master Higgins needs to ask permission from his captain, and he may not be able to take two passengers.”

“I think it’s a terrible idea for you to go to Canton, but if I can’t stop you, then I am going with you, and that’s all there is to s

ay. A lady like you must not travel alone, and you will need my help with the foreign sailors.” Pai Chu shuddered at the thought of sharing a ship with hundreds of the rapist devils, but she would do it for Su-Mei.

“Oh, thank you, dearest sister! You are very kind to think of me. But I cannot take you with me. It isn’t safe for you. If I’m arrested, they may take you too, and you are part of our family now.”

Nothing will stop me from following you to Canton, Pai Chu swore to herself. “All right then, Su-Mei,” she said aloud. “But promise me you’ll be careful.” She paused and looked away shyly. “You know how much I love you.”

“Oh, Pai Chu, I love you too! I’m so glad that we became friends, and now we’re sisters! If I escape the death sentence, I hope that we can continue doing God’s work together.”

Pai Chu felt a pang of frustration. Su-Mei didn’t understand. Pai Chu wasn’t sure she understood it herself, but her love for Su-Mei exceeded the love of friends, or even of sisters. We could live together, the stubborn thought arose, and I could take care of her better than any horrible foreign devil. He can’t love her—he can’t even understand her. Why can’t she see that? “Yes, my sister, I hope so too. Just remember that I will always be here to help you, whatever you need. And I will pray that you return safely to me.”

Su-Mei wrapped her arms around her friend in gratitude, but her mind was on Mr. Higgins. When will he return?

“Mr. Johnstone, I need your help,” pleaded Higgins. “Lord Lee, your Uncle William’s largest customer, has been arrested in Canton. His daughter, Miss Su-Mei Lee, is urgently requesting passage with us to try to help her family.” Johnstone frowned. “If we can help her,” continued Higgins, “it will go over well with her family and your uncle after the events at the Dragon Inn. This will blow over, like everything else does here, and we’ll want Lord Lee to be indebted to us when it does.”

Chapter Fourteen

Canton, early 1839

Special Emissary Lin paced in front of the kneeling hong merchants he’d summoned. “Shame on you all! You are letting this foreign poison ruin our beloved Celestial Empire,” he lectured. “I know most of you are only interested in legitimate export of our products to this faraway land, but you know very well that the British barbarians use opium as currency, so even if you’re not dealing in opium directly, you are complicit in what it is doing to our empire.”

“Honorable Big Lord Guan,” Howqua, the leading hong merchant said, “we are only interested in glorifying our empire by selling our excellent wares to these barbarian lands—”

“You dare patronize me with this nonsense?” Lin interrupted. “You have never, not once, turned away a foreign ship carrying opium, even though you are supposed to vouch for all vessels entering our kingdom. You allow these barbarians to use your factories for opium trading instead of whatever legitimate business they claim to be conducting. You accept bonds for our own silver—used to purchase opium—in exchange for your tea and silk. Please, Lord Howqua,” Lin glared down at the hapless merchant, “explain to me how you are glorifying our beloved empire with these practices!”

“Honorable Big Lord Guan, we are unwilling victims of the opium trade!” protested Howqua.

“And are you also unwilling victims when you collect the profits from dealing with these barbarians, knowing opium drives the entire business?”

There was silence in the room.

“And where is this taipan they call the Iron-Headed Rat, Lee Shao Lin’s supplier? I want him arrested immediately!”

“He is on his way back to his home country, never to return, Lord Emissary,” ventured one of the merchants.

Lin was secretly a little relieved to hear this. He wanted to punish the most notorious smuggler to send a message to the others, but he was unsure what the response from the barbarian kingdom would be if he executed one of their most prominent citizens. “Well, that is unfortunate,” he snapped. “Chief Inspector Cheng, you will please read the edicts aloud now.”

“Edict Number One,” read Cheng, “to be delivered to your British trading partners. All foreigners are to surrender any opium aboard any ship in Chinese waters, and they are to agree in writing that no further opium is to be shipped to China.

“Edict Number Two, to the attention of all hong merchants. You are all complicit in every aspect of the opium trade: You have provided boats to carry opium ashore and floating warehouses to store it; you have used Lintin Island to hide the ships anchored offshore; and you have committed money laundering by moving precious silver out of the Celestial Empire, even providing special standardized boxes for transport.

“You have acted as traitors to the Celestial Empire, and if you do not arrange for all your foreign trading partners to surrender their opium within three days, the special emissary will commence executions. You all know that Special Emissary Lin has conducted a long and thorough investigation of the opium trade in Canton, and furthermore, you know that the emperor has personally tasked him with halting opium imports to the Celestial Empire. Leave here now and act accordingly.”

The terrified hong merchants delivered the edicts to the Western smugglers in Canton that day. To prevent them from running off to Macau and ignoring his edicts, Special Emissary Lin forbade all foreigners to leave Canton until they were in compliance and posted guards to prevent anyone from leaving. The following day, forty foreigners held a meeting at one of the factories to discuss how they would respond—naturally, no one was eager to surrender any opium. Among them were James Matheson and Lancelot Dent, the second-largest smuggler after Jardine and Matheson. After a lengthy discussion, they wrote a message to the special emissary requesting six days to consider their response.

With fear in their hearts, the hong merchants delivered this message to Special Emissary Lin. They survived the encounter but returned to the factories the following day with chains around their necks, the emissary’s reply to the foreigners.

“It’s simple, gentlemen, really,” said Matheson. “We hand the bugger a few chests to think we’ve been chastened, and then when this rout dies down, it’s back to business as usual. What do you reckon, a thousand chests, split among us?”

But Special Emissary Lin knew precisely how many ships were anchored off Lintin Island, loaded down with tens of thousands of chests. “These foreign devils think I am a fool,” he muttered. “Inspector Cheng, take your soldiers and block all access to the factories. Hire some builders and erect high brick walls around every one. I don’t want the foreign devils to even be able to see out!”

“Lord Emissary, it will be done just as you say,” said Cheng. “But the foreigners are holed up inside—do you mean to trap them inside the compounds?”

“Yes!” roared Lin. “That is exactly what I intend. Their servants will abandon them, and the barbarians will starve. My sources tell me they have no stockpiles of food or water. They will have their six days and more! Then we can reopen the topic of surrendering the opium.”

Captain Charles Elliot of the British Royal Navy was appointed chief superintendent of trade in 1836, responsible for all British ships and subjects in China. Since most trade was conducted among British merchants, smugglers, and local hongs without supervision, there was little need for an official chief superintendent to protect anyone’s interests. He kept himself out of everyone’s way, stayed in Macau most of the time, and let the money roll in to English coffers—until Special Emissary Lin made his move.

At last, after he received word of what was happening in Canton, Chief Superintendent Charles Elliot found himself with something to do. He arrived in Canton on the announced arrival date of the special emissary, by which time his countrymen had been barricaded in the compounds. His first move was to sail up the river to the factories on a boat flying British colors with a platoon of uniformed marines, hoping the Chinese would realize that an attack on his boat could be interpreted as an act of war. He was, after all, a naval officer representing the Crown in China.

&nb

sp; Once inside the British factory, he ran the British flag up the pole, thereby declaring the compound British sovereign territory. His presence, for the first time, was welcomed by the smugglers; they suspected the special emissary would hesitate to provoke a confrontation with a senior British officer. And so began the siege at the factories at Canton, after decades of uneventful opium trading.

It was a few days before Special Emissary Lin made his next move. “Inspector Cheng!”

Cheng had just settled down to eat his dinner at a low table in Special Emissary Lin’s temporary headquarters. He had been hard at work since dawn. With a sigh, he set down his bowl. “Yes, my lord?”

“You will have a sign painted, the length of a man on all sides. Make the characters big enough so that everyone can read the message and translate it to the barbarians. The message should read as follows: ‘I, Special Imperial Emissary Lin Tse-Hsu, would prefer to solve this impasse without resorting to force. My demands are simple: All foreigners must surrender all their illegal opium to me to be destroyed and agree to bring no more of it into China ever again.’”

“Understood, Lord Emissary, and will comply!” Cheng gulped his tea and sped out the door, wondering where to find a sign painter at this late hour.

Charles Elliot swore heartily when he learned what was written on the large sign erected outside the compound. This special emissary was serious, and he wasn’t going to give in until the traders gave up their opium.

“I will simply tell the traders to surrender their cargo to me personally, not the special emissary,” he informed his master attendant. “The opium will thus become the property of the British government. I will then hand it over to this special emissary, and he will save face with his emperor. The traders may demand reimbursement from the Crown at whatever rate they choose, and so they will not be out of pocket. And, of course, any man who refuses to surrender his opium will not have government protection and so be at the mercy of this damned emissary.” He knew all the traders wanted, after profits, was for the crisis to end so they could flee to Macau and enjoy Western comforts at Eastern prices.

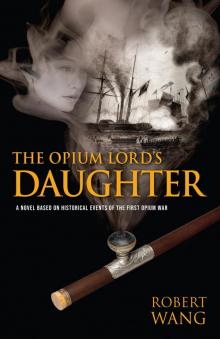

The Opium Lord's Daughter

The Opium Lord's Daughter