- Home

- Robert Wang

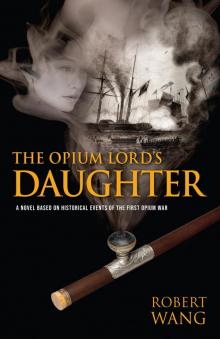

The Opium Lord's Daughter Page 11

The Opium Lord's Daughter Read online

Page 11

Pai Chu grew pale. “My air? I can breathe just fine!”

“No, silly,” said Su-Mei. “Your energy, in your body! He wants to make sure you don’t have too much yin, which means cold energy, or too much yang—you know, heat.” Su-Mei giggled nervously, enjoying the opportunity to be the teacher for once but also surprised that her friend, who was older and seemed so worldly, had never seen an herbalist. She hoped Pai Chu didn’t have any more questions, however, because she had offered up the extent of her knowledge on the topic.

“Miss Pai Chu must rest in bed for at least ten days so that her wound can heal and she can regain her strength,” Master Siu said at last. In spidery calligraphy he wrote out a list of ingredients that included ginseng, radish seeds, tangerine peel, and ten other mysterious substances for stomach ailments. He handed the scrap of paper to his assistant, who bowed and left the room at a run. “My assistant will return here with the proper herbs in a short time. Miss Pai Chu must take an infusion of them twice a day for all ten days. And now,” he said, rising from his stool, “for my examination of Lord Lee.”

“I need to return to Canton right away to check for any damage to my warehouses from this typhoon,” Shao Lin said as the herbalist checked his pulse. “I will have to hobble with a cane, but I must take care of things personally.” He thought for a moment. “Su-Mei, you and Pai Chu should return to Mother Amanda’s school so Pai Chu can recover. In ten days you will both come to Canton and join the rest of the family. I know you are desperate to return home, but Pai Chu saved your life, and it’s your duty to stay with her until she recovers.”

Su-Mei tried to suppress the grin on her face. “Honorable Father, I will of course stay here and do my duty for my sister, even if it means missing home and Honorable Mother. Which I do, so much.”

“Then it is settled. I will sail back this afternoon and return in ten days to take you and Pai Chu to Canton.”

The young women shared a glance, both thrilled by the news but trying not to show it.

“Yes, Honorable Father,” they replied in unison.

Mother Amanda was happy to learn that the plan to keep Sister Maria with Su-Mei had worked, although she was shocked and saddened to learn of Father Afonso’s demise. But there was little time to mourn—the convent buildings had suffered significant damage from the typhoon, and money had to be found for the repairs.

“While Sister Maria is recovering, Miss Lee, I must ask for your assistance in securing donations,” she said.

“Of course, Mother Amanda, I am so happy to be back here for another ten days, and it would be my honor to help the church.” Her father, she knew, would cheerfully pay for all the repairs and then some if she asked, but that might mean the end of her stay in Macau and any further interactions with the foreigners.

“Then we must write to our usual donors, but it would be helpful if we had something to sell or auction.” Mother Amanda paused delicately. “I don’t suppose you have anything of value? Jewels, perhaps? Jade objects?”

Su-Mei had another idea. “I could teach Chinese to foreigners—if someone can translate for me.” This would be the perfect way to interact with the Westerners and learn from them.

Mother Amanda stared. “That is a novel idea, Miss Lee, and certain to attract some interest. Many in Macau would be intrigued by the opportunity to learn Chinese from a noblewoman such as yourself. But are you certain—would your Honorable Father be quite amenable…?”

“Honorable Father brought me here to advance my education,” lied Su-Mei. “He would find this plan acceptable, providing I have a chaperone, of course.” One who speaks English and is already devoted to me and my family.

“Very well. We shall advertise Chinese lessons taught by a Chinese noblewoman.” Mother Amanda had a sudden thought. “Miss Lee, would you like to learn some hymns in English? You could sing in the choir, which would allow you to share your gift with God and learn English at the same time.”

“I…have never really sung before,” Su-Mei said. She recalled how she had felt at Mass when she heard the choir of beautiful voices and tried to join in. “But I would like to learn.”

Mother Amanda had a passion for music and poured it into the small convent choir. The nuns, a few lay sisters, and the female orphans who demonstrated a gift for it often sang together. They performed for themselves alone—and God—as women were not permitted to sing in front of a congregation of men.

Pai Chu translated two hymns into Chinese for Su-Mei and added notations on how to pronounce the English words. Su-Mei spent most of the night studying and memorizing the songs. By morning her English vocabulary and pronunciation had improved considerably. Learning new words and phrases made Su-Mei happy, but she could never have imagined the feeling of power that arose in her when she sang those hymns with the other women. She had never felt this way before and was overcome by the experience. She had already been touched by this Holy Spirit, but to sing praises to God filled her with a rare and acutely personal joy. It felt as though she was communicating directly with him, and his presence was in her heart as she sang. Tears were streaming down her cheeks when the choir finished its last Amen.

Mother Amanda witnessed this display of emotion and struggled briefly with the sin of pride. This is the Lord’s work, she reminded herself, for his divine purpose.

The Dragon Inn and the convent weren’t the only structures ravaged by the typhoon. Travers Higgins and the rest of the crew of the Scaleby Castle found themselves at leave in Macau until the necessary repairs to the ship could be made. As it was a Sunday, and the public houses that served Westerners were closed, they opted to attend a Catholic service, there being no Anglican or Protestant houses of worship in the enclave. A neatly hand-lettered sign in the sacristy advertised an auction that afternoon to raise money for repairs to the neighboring convent.

Higgins, anticipating a long, tedious sermon in Latin, was stunned to see the Chinese lady, Miss Lee, seated a few rows ahead. Why didn’t she depart with her father? he wondered. He entertained himself during the service by watching the movements of her graceful head and shoulders as she prayed and her delicate, pale hands as they turned the pages in a hymnal.

After Mass the congregation was invited to the courtyard outside the church for refreshments. Baskets of bread and cakes were sold, along with household items that had been donated, and then the auction began.

Works of art were the first items to be auctioned, and they sold at prices well above their worth. It was not unusual for homesick Westerners to give generously to missionary churches, and most Westerners in Macau were enjoying the considerable profits of the opium trade. After the final items were auctioned off, the mother superior of the convent made an announcement about some additional lots of particular interest. Johnstone motioned to the senior officers around him that it was a good time to go.

Higgins stood and began to follow the others out of the courtyard while the mother superior offered the services of her nuns and novices to clean the home of the highest bidder for one month. There were many large homes built with opium profits, and they needed constant tending in the subtropical climate. This item sold after fierce bidding and collected a handsome donation.

The second item was Chinese lessons to be taught by bilingual nuns. European ladies living in Macau were interested in learning Chinese so they could communicate with their servants and haggle in the markets, so those were snapped up quickly.

Higgins and the other officers were at the gate when Mother Amanda said, “A new member of our congregation, Lady Lee Su-Mei, has generously donated four hours of Chinese lessons per day for eight days. She is a noblewoman from Canton, and we are indeed honored that she is supporting our church.”

Higgins froze. “However,” Mother Amanda continued, “her English is not quite proficient yet, so our Sister Maria has volunteered to help translate for Lady Su-Mei. This would be a most diverting experience for the winner, who would not only learn about the culture of noble

Chinese families but also have the opportunity to help the lady improve her English conversation.”

“I say, mate,” said Higgins to Lieutenant Adams, the last officer still in the courtyard, who had turned around to see what was keeping him. “I’ll give you my privilege tonnage going back to England if you can lend me enough money to win this.”

Adams chuckled. “Are you mad, man? Your tonnage is worth a bleeding fortune back home! What d’you want to learn Chinese for, anyway? All the buggers speak English!”

“Just lend me the damned money, will you? It’s a bloody godsend for you, and you know it.”

“All right, Higgins, but I worry you’ve gone bloody daft. I’ll make a monkey off your tonnage, and no mistake.”

“And welcome to it, man. Now, quiet—I’ve got to place my bid!”

The bidding was not as robust as Mother Amanda had hoped, which suited Higgins just fine. For a little over ten pounds sterling, Lee Su-Mei was engaged to teach him Chinese for eight glorious days. He could hardly contain himself as he handed the money over to the mother superior and didn’t dare look over at Miss Lee. His tonnage was easily worth the five hundred pounds Adams had predicted, but spending the next week with this astonishingly beautiful Chinese lady was worth all that and more.

“Please follow me, sir, and meet your new Chinese tutor,” Mother Amanda said, cutting into his excited thoughts.

“Miss Lee, such a pleasure to meet you again. I am at your service.” Higgins spoke slowly and carefully.

Su-Mei bobbed her head, and blood rushed to her cheeks. “Sank yoo, sank yoo. I am onnahed to sehve yoo.”

“Indeed, Miss Lee, quite. The feeling is mutual.” Bloody hell, what am I on about? She doesn’t understand a word!

Mother Amanda explained that the lessons would be conducted in that very courtyard, with Sister Maria acting as translator and chaperone. Higgins nodded, agreeing to everything she said.

“Your lessons will begin tomorrow at nine in the morning, if that is suitable, sir?” Mother Amanda said.

“Yes, indeed!” Higgins reached out to shake Miss Lee’s hand, then pulled his hand back, suspecting that this was perhaps not appropriate. He bowed slightly instead. “It will be my pleasure to wait upon you at that time tomorrow, Miss Lee. Mother Superior.” He bowed again and stepped smartly to catch up with Adams, who was still shaking his head at Higgins’s folly.

“You’re going to teach Chinese to that no-good barbarian who almost killed me?” Pai Chu hissed when she heard the news. “I don’t trust him, Su-Mei. He looks at you in a very disrespectful and inappropriate way.”

“I’m sure that is not true,” said Su-Mei, wondering if Master Higgins had indeed been looking at her.

“It is true, Su-Mei—trust me! These brutes have only one thing on their minds. How do you think I came into this world? One of those foreign devils from an English ship forced himself on my poor mother. He ruined any chance she had for a good marriage and a happy life. I could never allow that to happen to you, my dearest.” Pai Chu’s voice throbbed with emotion. As far as she was concerned, all British sailors were drunken, vicious louts who attacked women. Hadn’t one tried to murder her only days ago?

“I think this one is different,” said Su-Mei. “He was polite to me at the inn and very sorry for what happened to you. I believe him when he said it was an accident. I am certain he won’t arrive for his language lessons drunk, and I don’t think he would do anything to hurt me.”

“Well, he won’t, Su-Mei, not if I am there to protect you.” Pai Chu laid her hand on Su-Mei’s arm, caressing it gently, while inside she seethed.

Su-Mei smiled at her friend, but her mind was elsewhere. Would Higgins continue to behave respectfully toward her, or was he just pretending to be honorable? Su-Mei didn’t know what to believe. Pai Chu’s mother’s experience was not that uncommon; but what she knew herself was that these were very interesting, brave, and seemingly reckless people who dared to cross vast oceans to come to her homeland to sell opium to men like her Honorable Father, who was making quite a lot of money from the exchange. Many people said the opium was a curse, but was its presence the fault of the foreigners or of men like her father? Or were the addicts themselves to blame? These questions were all so confusing! It was wrong, assuredly, to feel anything but the utmost respect toward one’s parents—or so she had been taught since childhood, but she was learning so many new things now: a new religion, a new language. What if everything I’ve been taught about the foreigners is wrong?

Chapter Ten

Canton, late 1838

Imperial Special Emissary Lin Tse-Hsu had been in Canton for three months performing his own private investigation into the opium trade. He had put together a small team of loyal investigators to gather intelligence, and they had presented him with a report that identified opium parlor owners in Canton, corrupt customs officials, Western smugglers, and the location of several opium warehouses in Canton. Lin’s official arrival date in Canton was announced as March 10, 1839, but the emissary preferred to avoid fanfare, and he wanted to see how the city really operated day to day, not the show the local officials would stage for him.

Only one year earlier, Emperor Dao Kwong had asked his Imperial Court, governor-generals, and senior magistrates to come up with suggestions for curtailing the opium epidemic. Level One Guan and Magistrate Lin Tse-Hsu’s recommendations were comprehensive and well planned; he emphasized attacking the Chinese end of the opium trade, arresting and punishing everyone from the wholesale traders to the pipe makers. Lin understood how the smugglers brought the drug in using corrupt officials in Canton, and his first recommendation was shutting down these foreign smugglers. Emperor Dao Kwong, realizing that Lin Tse-Hsu was probably one of the few truly incorruptible men in his court, made him a special emissary and charged him with ending the flow of opium into the country. Shao Lin’s father, Level One Guan Lee Man Ho, enthusiastically supported all of Lin’s recommendations, which played a role in the emperor’s decision to assign Lin as special emissary.

“Lord Magistrate Lin,” he announced in formal session before dispatching Lin to Canton, “as my special emissary and my most loyal guan, I hereby authorize you to rid our beloved Celestial Kingdom of this poison from the English Kingdom. We must remove the despicable corrupt guans and merchants who profit from this immoral and wicked trade. Therefore, I bestow upon you this imperial plaque, which authorizes you to act on my behalf. I urge you to show no mercy to the worst offenders—let us set an example for the English. Do not hesitate to punish our worst criminals with family extermination to send a clear message to all that the Celestial Kingdom will no longer tolerate the opium trade.”

An imperial eunuch took the plaque from the hands of the emperor and presented it to the kneeling emissary. It was carved from a single piece of white jade attached to a wooden back and tied to a silken cord dyed imperial yellow. Inscribed on the plaque was Lin’s name and “Imperial Special Emissary.” Below his name and title were the words “representing the Celestial Emperor” and a carving of the imperial seal to testify to its authenticity. No one seeing this plaque would question the authority of Lin Tse-Hsu.

“I understand and will obey, my most beloved Majesty Emperor,” replied the special emissary, a shiver running down his spine. Family extermination was the most severe capital punishment, in which the entire families of those who committed crimes against the kingdom or the emperor were beheaded in public to show there was no tolerance for treason. Special Emissary Lin Tse-Hsu knew without a shadow of a doubt that the emperor intended to rid his beloved Celestial Kingdom of opium once and for all.

Now in Canton, Special Emissary Lin was seeing for himself how everything and everyone in the trade were connected and who the worst offenders were. Public outrage against the trade had begun to grow; opium was ruining the beautiful city of Canton and giving it—and its inhabitants—a bad reputation throughout the Celestial Kingdom. The honest magistrates attempted to discourag

e smugglers, and some of their efforts met with success. Many of the small-time opium parlor owners and dealers were arrested and charged, but the major players continued importing and selling their wares unchecked, relieved that their rather large investment in protection was paying off.

When Emissary Lin read the final report, he had no trouble working out how the opium was smuggled into Canton—by way of Lintin Island and the floating warehouses; which officials took bribes to let it through—almost all of them; and how the drug was divided among the local dealers and parlors. Conspicuously missing was the identity of the man who acted as the local clearinghouse for pricing and distributing the largest shipments when they arrived in Canton.

“This report is inconclusive,” he snapped. “How can you not know the identity of the largest dealer when you have obtained every tiny detail about everything else?”

“Honorable Big Guan,” replied Chief Investigator Cheng, “we have our suspicions, but we are afraid to dig deeper without your permission.”

Lin tossed the report to the table in disgust. “My permission? Why do you need my permission to do the job I assigned you?”

“My lord,” Cheng replied, cold sweat forming on his forehead, “all our evidence points to someone whom we are afraid to offend, especially if we are wrong. So we must ask your permission before we proceed.”

“And who is this suspect?”

“Lord Guan,” Cheng hesitated. “It is…Lord Guan Magistrate Lee Man Ho’s son, Lee Shao Lin.”

Lin stared at the investigator. “Impossible! Are you sure?”

Cheng nodded miserably. “We have followed the movements of opium shipments from the largest foreign devil taipan, the man they call the Iron-Headed Rat—William Jardine.”

“Why is he called that, Chief Inspector?” interrupted Lin.

“The story is he was hit on the head by a local but completely ignored the incident as if it had never happened, Lord,” Cheng explained. “Once the opium gets past the corrupt customs officers who are taking bribes from the foreign devils—and by that I mean all the customs officers—we traced it to where it’s warehoused before being distributed to local dealers. All evidence points to a group of dealers who work for a tea and silk company owned by Lord Lee Shao Lin. If this is true, then Lord Lee is the biggest opium dealer in Canton and using his tea and silk store as a front.”

The Opium Lord's Daughter

The Opium Lord's Daughter